Catching Up in the Archive

Tafelgast: Dear Friend

Dear Friend is een maandelijkse publicatie in briefformaat over ontwerpgebeurtenissen, problemen en ideeën. De publicatie die via snail mail wordt verspreid, is een initiatief van Sandra Nuut en Ott Kagovere en wordt ondersteund door de afdeling Grafisch Ontwerp Estonian Academy of Arts. Sandra en Ott schonken de hele collectie Dear Friend aan de Appel Archive.

Zie het transcript van hun gesprek bij de Appel hieronder.

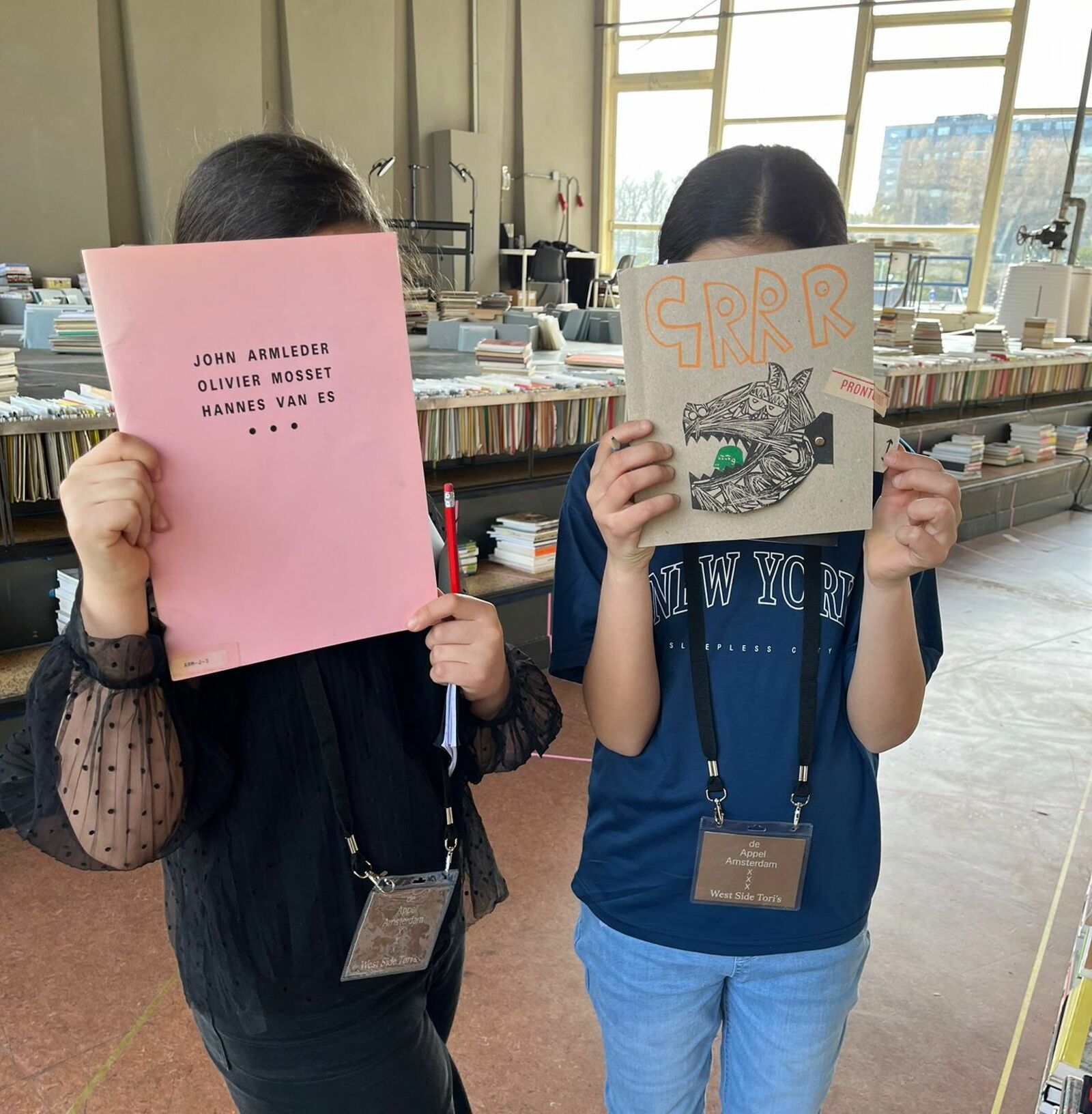

Ott Kagovere met alle edities van Dear Friend.

Sandra Nuut, Ott Kagovere, het team van het Archief en Mariana Lanari.

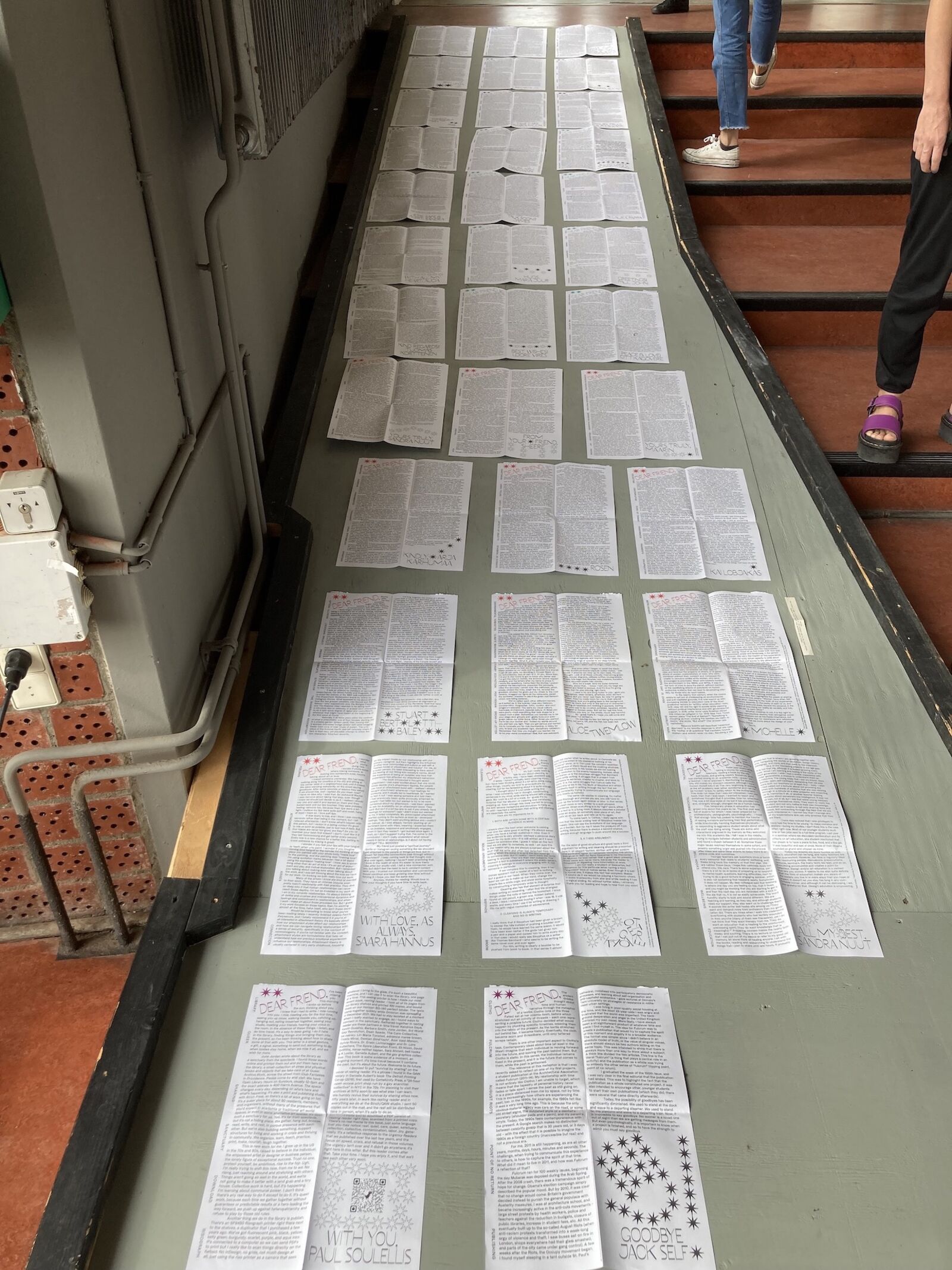

Alle uitgaven van Dear Friend die aan de Appel zijn gedoneerd.

Transcript of Dear Friend in Catching Up in the Archive

13-04-2022

Ott Kagovere & Sandra Nuut have a talk with Nell Donkers at de Appel

Ott: It's very interesting to write about design related issues, and we do it in a very odd, let's say, unacademic format. And that's also one of the reasons why we chose this letter format. Because it's very, you know, it seems very easy, in a way, and non-pretentious. So, let’s say, if we would approach a graphic designer, and tell them to write an essay or an article, then of course, if they are not writers, they will say that they are not into it, because they don't know how to do it. But if we say that it's just like, you know, it's almost like a blog or something, like a longer tweet, then it seems somehow, you know, actually interesting. So in that sense we chose this kind of format, but also because it plays around with the physicality from the start.

At the moment, we have this website and archive where all the letters are, but this is actually quite a recent development, we have it maybe for a year or two.

Sandra: Maybe I can add, you mentioned that there was this need for design writing, or on visual culture, but it’s very broad. So it’s not only design or art, it’s basically people working in the design field writing on whatever is connected to them. I think there was a lot of discussion around that there is too little writing happening. So one of the goals was to put into some kind of writing into it. But there was also a very personal need to have a community, a kind of network. Who are the people around us?

Because Dear Friend is not local at all, there are people writing from all over the world. The basis is in Tallinn, but if you look, the letters come from everywhere.

O: Yes, also half of the editions are send out to different countries.

Nell: How does it work? Do people take subscriptions? Or do you choose the people you’re sending it too?

S: There is not a subscription as such, and it’s for free. And, as I mentioned, there was this feeling that we could be in touch in some way with our network. So that’s where the format also comes from. But yes, we chose people, institutions, or just some basic different locations that we feel are somehow connected to us.

O: Yes, for example, either someone who has been to the design department to teach, or you know, we had some friend teaching in a school in another country and we send it to them over there. So there is somehow this selection, this invisible community of people.

But also about the subscription, quite often people write to us and say that they would like to subscribe, but we have almost always declined. A friend of mine is doing a bookshop in Finland, for example, a temporary bookshop, and then she also asked if I could send them like more letters so they could give them out there or sell them. But we have declined because, you know, we really do this as a side project, a passion project one might say. We don’t get paid for it. So we don’t actually want to grow because it’s so easy to outgrow what you can do. And the project basically dies because it becomes too big for you to handle aside of all the other work that we do. So it’s a very conscious decision. We have a surplus of like 50 letters that we have in the graphic department to pick up for free. Or in some book shops and places where we leave them almost as free flyers. But basically, we don’t have this idea of making it a huge thing. The fact that we’re here is also kind of like a random, you know, accident, I would say it’s not necessarily like a publicity stunt or some type of advertising, it just happened that we’re here.

S: There’s plenty of people receiving it, and a bunch of people who can just take it.

N: So, first of all, I’m really proud to take this into the archive of de Appel. Like, all the issues you have been publishing , and writing and sending. I was wondering, in your international network, how do you choose? Because I think there is also this connection with The Remote Achivist somewhere, this magic of how you came here.

O: Well, the way we found you was, I guess, because I know Bardhi Haliti who was doing The Remote Archivist with you, and we like this project. And also, it’s very similar in nature, because it’s letter based, like letter sending. Its like a small, local micro-publication.

Also, somehow, this idea of having a bigger ritual, and some kind of letter and stuff like this. So in that sense, we thought that perhaps the projects has some kindred spirit, so that’s why we thought of reaching out.

And at the same time, again through this kind of imaginary community, you know, knowing Bardhi seeing this thing on Instagram and basically then subscribing to it and receiving some issues and then thinking maybe it would be nice if you would write a letter about your project.

S: But your question was also how we select writers? It’s usually one way, so sometimes there is some kind of topic or project that feels relevant, or the time feels right for someone to write something, and then there are projects that somehow feel relevant at that moment. It’s a specific way of approaching. There is like that feeling, we call it a feeling.

O: You could say also that maybe, now you actually think of it, maybe there are like two ways. Like one is, of course, this personal way, like, I don't know, someone comes to teach and we like their practice. And then I said, would you like to write that? And they are like, sure. But sometimes it's also someone we don't know, actually, and then we would like to have, let's say, a conversation with them. And then we write to them, and quite often it works out because they're like, oh, yeah, sure. But I think it's also because this, you know, we print on a big paper, but actually it's a very small you know, in word count. It's a very small letter, like one and a half A4 or something like that. So it's just like a small thing.

N: I wanted to ask you, what do you think about the stamping? Because I feel like The Remote Archivist is a lot of work, and handling it really comes down to the material. And then also, how do you pay for the post, for example?

S: Yes, so putting together the letter is basically like a workshop. Every time a letter is going to be published, its like, we gather and fold them, and then also, within the framework of the university, there is someone who will do the stamping for us.

O: That’s actually something to, like, emphasise. Because we are both working in the university. So we have the ability to use some of the resources which is actually what makes this project possible. Because, we don’t really have any funding, I mean, we have a little bit now. But when we started what made this project and sending it possible at all, was that each department in the school can send out post for free, like if they need to send a contract to someone for example. But nowadays this does not really happen, because everything is online. So now it’s like one letter a month that they are sending. But, no one really checks. They wouldn’t think that someone would send out 200 letters each month, but because no one checks, we can do it for free. So in a sense by using this like parasitic way of distribution, we can do this and many other things. Printing is for free because we have a riso printer at school and other obvious things.

So basically we are using all the possibilities that are out there, that we can use for free at the moment. Maybe if we in the future don’t work at the school anymore the project also dies out. So it’s just making use of the things that we have at hand anyway.

N: We're now in Mariana Lanari’s Catching Up in the Archive, and you can find a lot of mail art from the 1970’s here. Did you start from that point? The Remote Archivist really started from like, sending things to your friends to let them know what you're doing, but of course, this is not necessary anymore, but I think you still miss these things in your Postal box.

S: Maybe for us the starting point was a bit different, it is not exactly the Mail-art but I guess we can connect it to this. When we started the first approach was not that it’s a letter actually. We were thinking of ways to write that was also achievable as a project. So that’s why it became one page that we could actually do it next to everything else. The last letter, right now, is published by Jack Self, he is an architect who was a student at the academy and he published Fulcrum which is also an architectural association in London.

O: First it was just a publication, and we thought about these practical things, like we make it in a way that it fits in one page so you don’t have to think about binding two pages together. You can just fold it and basically then it looks like a letter. And then from there the means of distribution comes in which is just sending it by mail. And then this physicality and personal things came into play which also has some nice connotations, so then we thought, why don’t we the write the letter, just physically. I guess that’s how it all came together.

N: I think this is nice because I see this happening a lot now. People are really going back to basics. Martha Jager also started a project here, its called Dear, its kind of the same way of working, and she also has this handmade quality. It can be a collage or with needle and thread even. It is nice, I will show you later.

Artemis Christidi: How do you pick the designs?

S: In the very beginning each letter writer chose the image, it was very basic. And now it changed a lot. Later on we started to invite very young designers, basically our own graduates. Because, we like them to have the opportunity to have some kind of platform so that their work can be seen and circulated.

N: is it always black and white, or also in colour?

O: Each season, so to speak, has its own colour. In the beginning of each year we order like 1000 or more empty sheets, in offset, where they only print the specific colour in the corner. So we already have them for the whole year. So this is the only thing that stays the same throughout each issue, and then we just print with risograph in black and white. Maybe, you know, you could do colour with risograph but we just don’t have the time. Which is the same as money, which we also don’t have.

Jacquine van Elsberg: Is there a maximum of words?

S: Yes, it’s 1000 words, and always in English. So some letters are a bit shorter, some of them a bit longer, but it can fit 1000 words approximately. And there’s an editor for the English language, so when someone writes a letter we first discuss it with the person who has written it,

O: So we talk about the content

S: Yes, maybe some point can be elaborated or something. But the grammar of the English language is edited by one person who has worked with us since the beginning. We have never seen her in person. So that’s also very interesting, that we are in mail correspondence.

Mariana Lanari: It’s really nice, I’m looking forward to reading all of them. And I wanted to know, maybe you already said, when did you start it? And if there's any intention of having some sort of a compilation, like even if it's online, that you can sort of read through all the letters?

O: This is the website for now. But also in September, we're doing like an exhibition in Talinn about the whole project. And we will publish a catalogue with all letters. So all the four seasons will be will be in the book, we will publish it with an Estonian small publishing company called Lugemik, and it will probably be out in September.

N: Will it also be Riso printed?

O: No, no

N: You know, I didn't have time to read them yet. But I feel that if you say to people write a letter, they go personal right away, because it's a letter. Do the writers reflect on that?

S: yes, because like, how do you go about writing something? It often happens when you start writing about something that it comes out differently from what your idea was. You might have some picture in your head, but the letter will just take you somewhere. So it can be very unexpected where you go with it, that happens quite a lot.

O: It is interesting to see how people interpret like the question ‘write us a letter’. We usually give some kind of input, but then how do people interpret it? We've had these situations, like we had like three or four letters in a row, where people have really taken this opportunity to write about like, almost their personal problems. And we don't mind this, it's completely fine, but it's just interesting to see. But some people take it completely the other way they make a fictional letter and devise a special character to write this letter from. So it is very interesting to see how people actually take this assignment.

N: Because it's dear friend, for me, it makes it that you write it to your friends instead of your enemy.

O: Dear Enemy,…