Lydia Ourahmane: Survival in the afterlife

de Appel, Schipluidenlaan 12, Amsterdam

The Consortium Commissions*

Survival in the afterlife

Lydia Ourahmane

Printed photos from the House of Hope Archives (1989 - ongoing) of Lydia Ourahmane

Opening with ‘purgatory beans’ cooked by the artist and friends

21 September 2021 at 19:00Exhibition

22 September – 23 November 2021Opening Hours

Wednesday to Sunday 14.00 - 19.00

De Appel is honoured to present the first solo exhibition of Lydia Ourahmane in the Netherlands. This exhibition, realised as part of the Consortium Commissions, initiated by Mophradat, became an opportunity to organise an archive comprising photographic materials, moving images and oral documentation – all produced alongside the constitution of an active spiritual movement and community her family founded during the civil war in Algeria (1991–2002). “These materials, which have remained within my immediate family, are testament to a spiritual movement that occurred behind closed doors, and for a period of time, in secret, in the basement of our various dwellings, which were then repurposed for a growing community of people,” writes Ourahmane in the midst of production. “Many of [these people] faced persecution back home and within the larger context of society. This is the reason it became a commune, not by recruiting per se, but rather determined by the urgency of survival, in the context of a civil war.” With this endeavour to gather, digitise and catalogue copious photographic documents produced by her parents and other members of a Christian commune, which came to be named the House of Hope, the artist makes these sensitive materials publicly accessible for the first time. How might this archive become a case study for investigating the changing conditions of belief at the intersection of religion, geography, politics and faith?

There are specific conditions for viewing the House of Hope Archives: gloves supplied to handle the archive will afterwards become part of its holdings, “underscoring the role of the witness.” Before reaching this archive, visitors are immersed in a sonic environment, an electronic sound composition realised in collaboration with Yawning Portal. Notice the direction of fires creates a world, a womb for nascent ways of living. Described alternately as “music to levitate to” and “euphoric ambient structures”, Yawning Portal is the collective name for two musical collaborators based between Chicago and London. In their work with Ourahmane, they conjure a landscape (using synthesised tones, foley effects and a recorded and repeated incantation), which is transmitted inside de Appel’s Aula through an optimised speaker system. Here the artist has made mattresses available to facilitate listening to the album-length composition. The title, Notice the direction of fires, alludes to the keen attention required to navigate an unknown landscape, where smoke appears as an indicator for the path of an invisible fire.

There is one element in the exhibition that is meant to disappear. Over the summer of 2021, Ourahmane has made a series of related sculptural elements – ciphers of conversations, measures of time spent – with collaborators, friends and family. What appear as hand-sewn pillows are also the foundations of a material language. These silent, sealed forms carrying the common title Closures are made to be taken away in time.

Lydia Ourahmane: Survival in the afterlife, eve of the opening at de Appel, Amsterdam, 21 September 2021 (Photo: Jimena Gabriella Gauna).

Lydia Ourahmane: Survival in the afterlife, eve of the opening at de Appel, Amsterdam, 21 September 2021 (Photo: Jimena Gabriella Gauna).

Lydia Ourahmane: Survival in the afterlife, eve of the opening at de Appel, Amsterdam, 21 September 2021 (Photo: Jimena Gabriella Gauna).

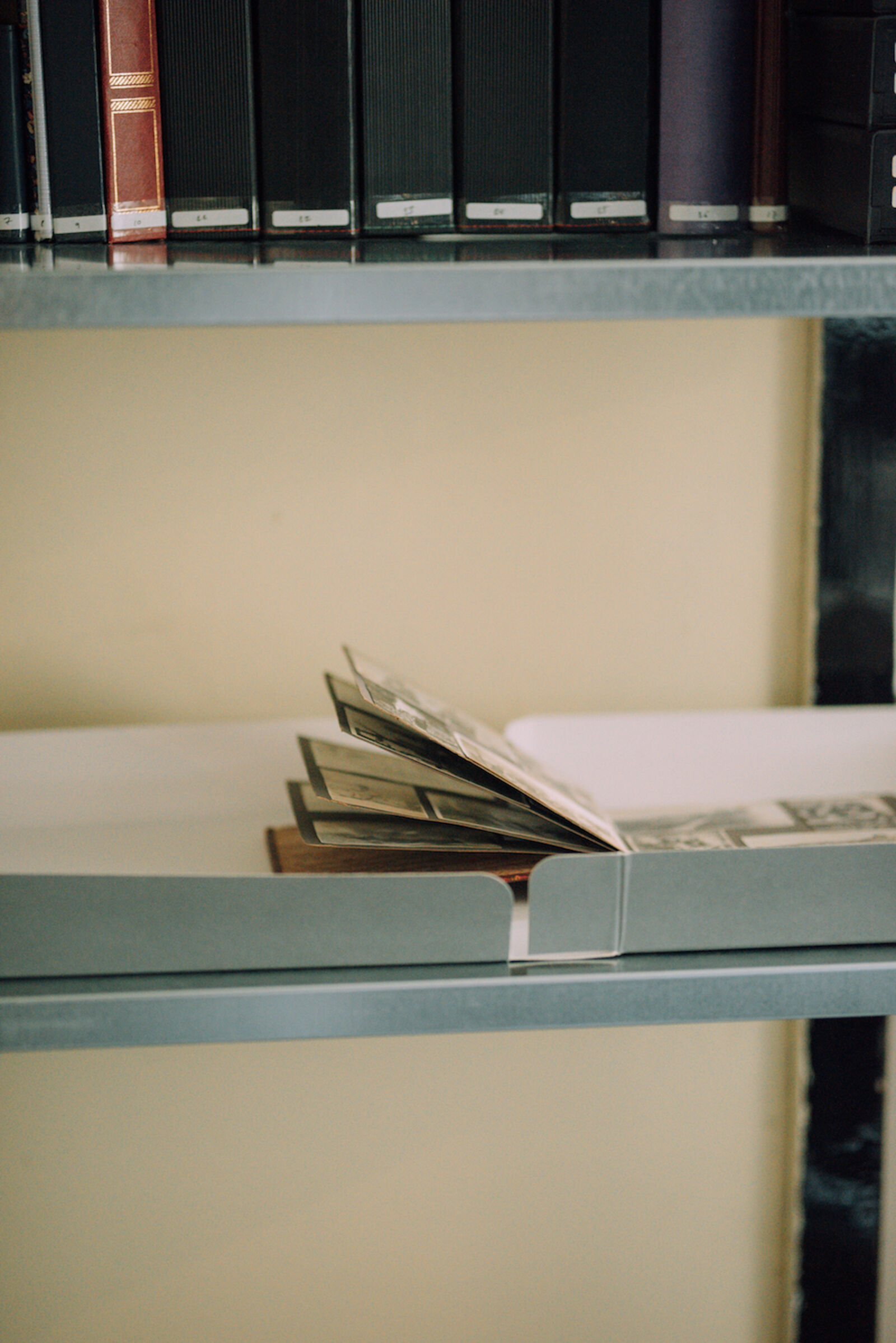

Lydia Ourahmane, House of Hope Archives (1989-ongoing); installation view (opening 21 September 2021) Survival in the afterlife at de Appel, Amsterdam.

Shelving, diaprojector carousels, light table, slides and printed photographs in archival sleeves, emptied albums and slide boxes, used gloves of all witnesses. Dimensions variable.

Photo: Jimena Gabriella Gauna, courtesy of de Appel.

Lydia Ourahmane, House of Hope Archives (1989-ongoing); installation view (opening 21 September 2021) Survival in the afterlife at de Appel, Amsterdam.

Shelving, diaprojector carousels, light table, slides and printed photographs in archival sleeves, emptied albums and slide boxes, used gloves of all witnesses. Dimensions variable.

Photo: Jimena Gabriella Gauna, courtesy of de Appel.

Tear catcher, circa 400 B.C.

Blown glass, 12x2.5cm. From the collection of Lydia Ourahmane.

Lydia Ourahmane, Survival in the afterlife at de Appel, Amsterdam 2021

Photo: Jimena Gabriella Gauna, courtesy of de Appel.

Lydia Ourahmane, House of Hope Archives (1989-ongoing); installation view (opening 21 September 2021) Survival in the afterlife at de Appel, Amsterdam.

Shelving, diaprojector carousels, light table, slides and printed photographs in archival sleeves, emptied albums and slide boxes, used gloves of all witnesses. Dimensions variable.

Photo: Jimena Gabriella Gauna, courtesy of de Appel.

Lydia Ourahmane, Survival in the afterlife at de Appel, Amsterdam 2021; exhibition view. Photo: Jimena Gabriella Gauna, courtesy of de Appel.

7 questions for Lydia Ourahmane

Would you say something about the atmosphere you experienced as a child during the foundation of the House of Refuge and the House of Hope?

I really think about the role of the witness – and my experience as framed within that. A witness often does not have a choice in what they experience, they just happen to be there at the time, in the same room. They immediately become a part of that narrative, their presence marks the potential for that story to continue, they become the point of reference, they become the voice. And there is a huge responsibility in the act of speaking something into existence. Sometimes witnesses refuse to come forward out of trauma or the fear of retaliation. I know that is quite extreme but for many many years I actually didn’t know how to find the language to talk about these experiences. As complicated as they are, I think they have a lot to teach us. Now, I feel like I am encountering this archive for the first time alongside the audience who share the responsibility of the witness.

You mentioned the title, Survival in the afterlife, is shared with your sister’s dissertation…

My sister, Sarah Ourahmane, is currently writing her thesis in the study of social and cultural anthropology at University College London, for which she conducted periods of research with many of the early converts who were present during the ‘first revival’ that actually happened during a football tournament in the Kabylia region of Algeria in the 80s. And it began with one of the football players experiencing a ‘miraculous healing’, which led to many people ‘believing’. She was particularly looking at the way that dreams, visions and healings underscored the wave of conversions at the time. She recorded hours of testimonies with many of the people who ended up with the House of Hope for many years – and who also became leaders of other large churches and communities within that region.

How has this community survived?

This religious minority continues to face on-going politicised oppression. A lot of these spaces were closed in 2017, the year a foreign infrastructural economic deal came into place. We can speculate that part of this had to do with the wave of conversions (from Islam to Christianity) since the 1980’s. The conversions were raising the vital statistics of religion in the Algerian population to almost 1% (Christian). At 1%, the government has to recognise Christianity formally as a practiced religion within contemporary Algeria. Now there is a push to reverse the 2006 law regarding freedom of religion and congregation, which my father fought for along with 3 other leaders who were sentenced to jail before their plea/campaign was backed by the international community. The international support further complicates this situation in terms of Algeria’s ongoing quest for de-colonisation. What we can see in the archive is how all of these people came to be under the very specific conditions of civil war, again a context of conflation between political and religious arguments. ‘Finding God’ and in turn kin, shelter, etc. became as much a mode of survival as it was a counter cultural movement. This is my sense of the situation as a witness.

What of the believer?

Spending time with this material has forced me to think about the potential for belief to transcend the parameters of the everyday. What we see in these images – joy, sharing, community – was completely opposite to the conflict that was happening outside of that environment. What were the conditions that enabled this? I also realise that the nascent moment (in this iteration of the archive) was a particular case to study, as the situation is quite different today. Something to reflect on from this moment of late-stage capitalism.

Conversion narratives, characterized by ‘meeting God’ in some capacity, provide us with the tools to consider the miraculous and the sacred, which occupy a different economy of space and time. I have also been thinking about how newly adopted belief systems might enable you to rewrite your own understanding of history, in non-linear time.

How do we understand this in relation to your artworks?

Oftentimes sensitive materials are only able to come to light after the period of time that they remained underground, so to speak. Their exposure means that they are now able to exist. I understand the work to be the decision to bring certain images to light. And this conversion to light is such a contentious topic because there is no side to take. Some might think about religious conversion as colonial conquest, which historically it is. But here, this community sprung from the depths of a civil war, and we must also consider economy as a factor within that conversation. For many people it was a place of physical, spiritual and emotional support.

Regarding Closures, what do you mean by ‘closure’ and what kind of other economy is at play?

The pillows were sewn with friends and family who were coming to visit me in my home the past few months. It was important to spend time after being apart from many of them for so long. I asked that each person bring something that they wanted to move on from, materially, symbolically, actually to sew this into the pillows. A lot of the time there were stories that they would tell me and we would sew them into the pillows. By speaking them into the very materials they become the object that someone can hold, a very strange and magical gesture. And in their repetition, they became quite ritualistic. For something to have closure it has to move on, physically. I think it does have to move, or find another way to exist. And not only necessarily as in discarding. I realised that they had to be taken away. Otherwise they would suffer from a kind of retention.

Notice the direction of fires, the sound composition you have realized with Yawning Portal, is the first work that people encounter. How would you describe its direction?

The composition attempts a reading of the collective consciousness by confronting its listener with a memory they may not even realise they have.

Would you say something about the way all this work is similar to previous works you have made, but also very different?

This feels like the most intimate work to date.

Born in 1992 in Saïda, Algeria, Lydia Ourahmane lives and works between Europe and North Africa. She graduated from Goldsmiths University of London in 2014 with The Third Choir, an installation that involved the first instance of the exportation of an artwork from Algeria since the country gained independence from French colonial rule in 1962. Thereafter she continued to test the possibilities for charging and converting the elements of the physical world as these move between borders, generations and dimensions. With works such as In the Absence of Our Mothers, presented at Chisenhale Gallery in 2018 and Barzakh, presented in 2021 at the Kunsthalle Basel and Triangle-Astérides in Marseilles, Ourahmane’s evolving research and practice continue to raise key questions about the connections between spirituality, contemporary geopolitics, migration and the complex histories of colonialism.

With special thanks to Jessica Mai Walker, Joe Ware, felicita, Sophia-Al Maria, nifnif, Alessandro Bava, Robert Fox, Cory Scozzari, Huw Lemmey, Arash Fayez, Isabel Valli, Steph Hartop, Saad Kabbara, Víctor Ruiz Colomer, Alex Ayed, Jeano Edwards, Youssef, Hie Tee and Sarah Ourahmane.

* The Consortium Commissions is a project initiated by Mophradat. The exhibition at de Appel is presented in partnership with Portikus, Frankfurt. Additional thanks for in-kind support by de Ateliers.