Felix Hess "Croaking and Chirping"

10.11.1983

Nieuwe Prinsengracht 33-35hs, Amsterdam

Nieuwe Prinsengracht 33-35hs, Amsterdam

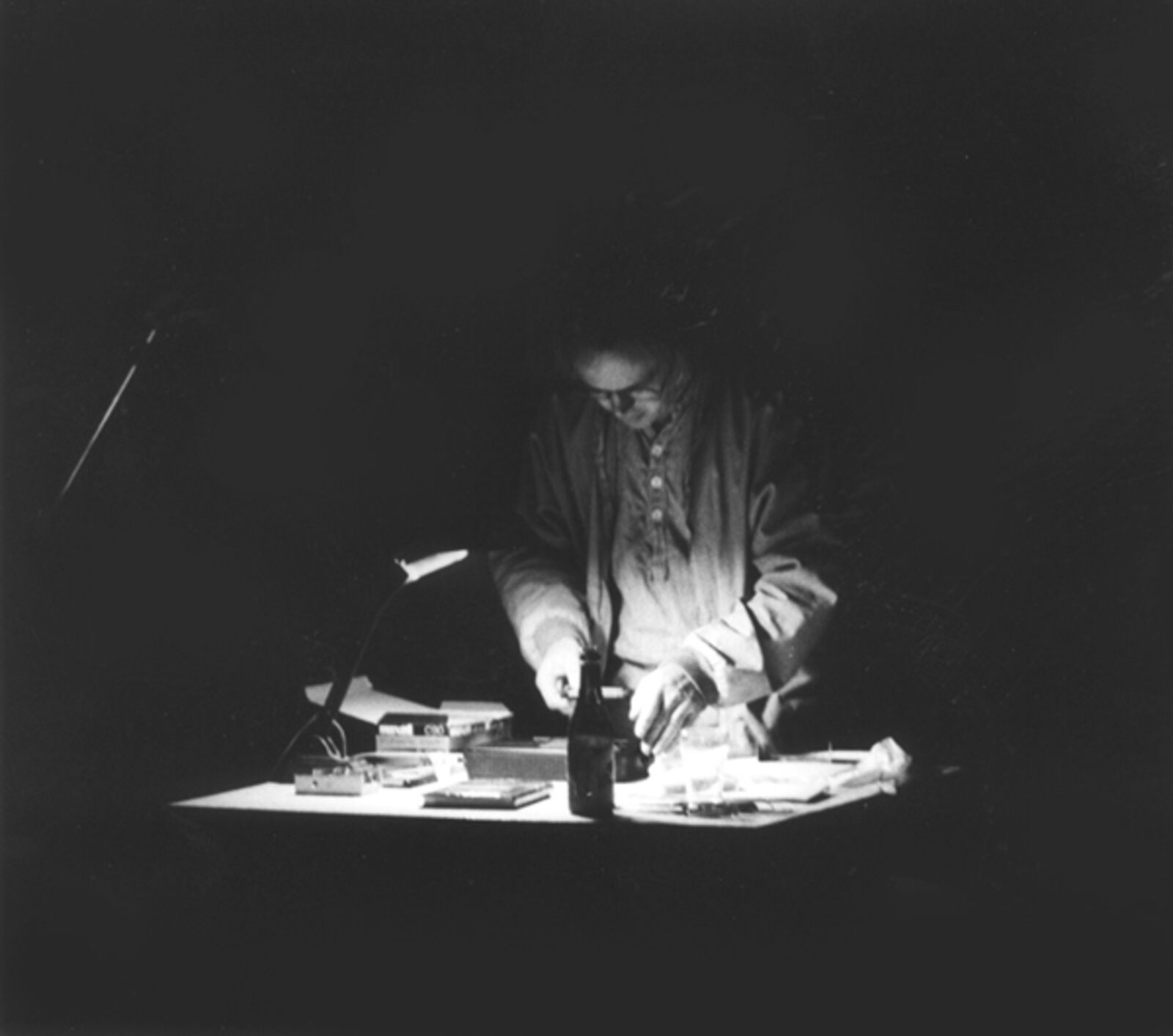

Live performance of the frog chorus by Felix Hess, Nieuwe Prinsengracht 33-35hs, Amsterdam I

© Max Bruinsma

© Max Bruinsma

Live performance of the frog chorus by Felix Hess, Nieuwe Prinsengracht 33-35hs, Amsterdam II

© Max Bruinsma

© Max Bruinsma

Live performance of the frog chorus by Felix Hess, Nieuwe Prinsengracht 33-35hs, Amsterdam III

© Max Bruinsma

© Max Bruinsma

Live performance of the frog chorus by Felix Hess, Nieuwe Prinsengracht 33-35hs, Amsterdam IV

© Max Bruinsma

© Max Bruinsma

‘What is it in the croaking of frogs that keeps me listening so intensively and completely? There exists an amazing variety of calls: frogs may croak, chirp, click, rattle, whistle. But it is not the individual calls that define my attention - it is the frog chorus as a whole, the pattern of calls in time and space, the wavelike movements of the sound, the rhythms. Also the balance between order and randomness, chaos. The sound of leaves rustling in the wind and the sound of waves rolling onto a beach are similar in these respects, but there is also a difference. Unlike the sound patterns created by a multitude of tiny objects under the influence of wind or rain, the main rhythmic structures in a frog chorus result from interactions between the individual callers. Similar patterns can be heard with some insects, such as crickets and grasshoppers. When listening to a frog chorus one may become aware of several rhythms easily, but the details of the sound patterns are unpredictable.

There often is a great beauty in the sound of a frog chorus, but it is not music. Music is sound made for people to listen to. Frog calls serve as a means of communication between frogs. (They must propagate. The males call and interact acoustically, and their calls attract the females.) The playback of a recording to a human audience, however, can be music. A stereo tape recording of a frog chorus captures much of the sound patterns, but some of the spatial Quality is lost. Also, a recording has a definite begin and end, whereas a real chorus continues indefinitely, with a diurnal rhythm and even an annual rhythm. And there is a lack of something utterly fundamental. The essence of the moment of listening, THIS moment in time, is absent in any recording: the 'past' and the 'future' have been arranged already along the tape .

I chose a second, very different, path from frog chorus to music. I concentrated on one feature: the acoustical interaction between the callers. It seemed to me that a relatively simple mechanism might account for some of the most fascinating aspects of. a chorus. This thought led to the design of electronic 'sound creatures' , which are capable of making their own chorus. A set of devices which listen and call. Each one reacts to the sound environment, which is partially created by themselves. The more conspecific calls it hears, the more eager it gets to call. Other sounds (human voices, footsteps, traffic noises, a slamming door) make them shy, and they may fall silent. A first version of such a group of sound creatures was built for me by the STEIM foundation. The listen and chirp, and so generate a real chorus. The process of the chorus in time is determined by the spatial distribution of the creatures, the acoustic properties of the space and the ambient sounds (and hence by the behaviour of the audience).

Of course, the complexity of the electronic creatures is nothing compared to that of any live biological system. Nevertheless, they may serve as a model in the scientific sense. Some biologists who are interested in the mating strategies of frogs have studied the vocal interactions between calling males. They found, for instance, that in some species a couple of males may form a duet by strictly alternating their calls (the males of a katydid species do the same), or that the proportion of males that actually call in a chorus drops as the density of callers increases. Apparently it becomes less worthwhile to call under such circumstances, and some males may prefer to silently intercept a female on her way to an active caller. Biologists have employed chirping machines and frog-call synthesizers in their experimental investigations. Likewise, a synthetic chorus could be used for scientific purposes.

The present 'electronic chorus' consists of some 36 identical (with slight variations) little machines. Each one is battery operated and contains a loudspeaker (= mouth) and a microphone (= ear). Basically they work as follows. The sounds that enter the microphone are to be interpreted as 'good' or 'bad' . 'Good' is sound recognized as a conspecific call. Operationally it is what passes through a recognizing filter. It is fed to an integrator and makes its level rise. All other sounds are deemed 'bad' and fed negatively to the integrator, making its level fall. The integrator is the machine's emotional centre, its level is the creature's 'eagerness' . When this eagerness reaches a critical level, the call generator is switched on. Now the loudspeaker emits a call, the integrator is discharged, the eagerness drops sharply and the call is switched off. Since the creatures are to recognize each other, the recognizing filter and call generator must fit like a lock and key.

I see these machines as a first stage, and intend to develop creatures which respond to a wider range of stimuli (e.g. light, temperature, direction of sound) and have a richer repertoire of vocal expressions. Eventually such machines might be constructed to move about: a beginning of dance in response to the perceived environment.’

(Felix Hess, ‘Croaking and Chirping’, De Appel, 3 (1983) 3, p. 18, 19.)

A live performance of the frog chorus by Felix Hess was presented by De Appel on November 10, 1983. Location: Nieuwe Prinsengracht 33-35hs, Amsterdam.